If you need this page in another language, please head to: https://translate.google.co.uk/. For further accessibility options and guidance, please visit: https://www.dbth.nhs.uk/accessibility/

Foreword

I am pleased to present Doncaster and Bassetlaw Teaching Hospitals’ (DBTH) first Health Inequalities Strategy, marking a significant step forward in our commitment to working to address the disparities in health outcomes within our communities. This strategy is a testament to our dedication to the principle that everyone deserves an equal opportunity to live a healthy life.

It is completely unreasonable that someone’s ethnic background or place of birth could be a determinant of their health. The urgency of DBTH’s mission to address this is clear within the statistics, which shows over 40% of the Doncaster and 21% of the Bassetlaw populations live in some of the most deprived circumstances. Life expectancy for both males and females in these areas is lower than the national average, with many living for many years of their lives in ill health.

This strategy is our proactive response to these challenges, acknowledging the societal, economic, and health system costs associated with health inequalities. The strategy recognises the need for a fundamental shift in the way we operate, emphasising the importance of targeted support based on individual needs. By addressing systemic barriers and focusing on equitable access, we can make substantial strides in reducing health inequalities.

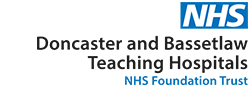

Aligned with national and local plans, to avoid duplication and to maximise collective resources, the strategy outlines key focus areas for the next five years, covering prevention, elective care pathways, urgent and emergency care, maternity and best start in life, children and young people, and research and innovation. It also focuses on enhancing awareness and understanding of health inequalities among our staff.

In line with the nature of the strategy, this is the first of our strategies developed to be fully accessible; meaning it can be put into digital software, such as a screen reader, or translation software, and be converted to be understandable format for a range of communities, something we are committed to do with all future strategies.

Thank you to everyone involved in shaping, reading and committing to the delivery of this strategy. It reflects our shared commitment to a healthier, fairer future for all of our communities.

Sincerely,

Richard Parker

Chief Executive

Doncaster and Bassetlaw Teaching Hospitals

Executive Summary

Health inequalities are “avoidable, unfair and systematic differences in health between different groups of people”. They mean that some population groups have significantly worse health experiences and outcomes than others.

These differences can be due to a range of factors including a person’s social, economic and environmental circumstances – and we know that greater deprivation in any of these factors is associated with an increased risk of becoming ill earlier and dying younger. People with certain characteristics, such as certain ethnicities, sexual orientation, age, and disabilities, also have a lower chance of living a long and healthy life compared to others. This is often due to the exclusion from society that people with these characteristics face.

At Doncaster and Bassetlaw Teaching Hospitals Foundation Trust (DBTH) we want to do all we can to tackle unfair health inequalities so have developed this strategy with the aim to embed the reduction of health inequalities in everything we do to ensure equitable access and excellent experience, thereby providing optimal outcomes for our patients and the communities that we serve.

In order to achieve this aim, our strategy has set out 6 priority areas of focus which include:

- Prevention

- Elective care pathways / recovery

- Urgent and emergency care pathways

- Maternity and best start in life

- Children and young people

- Research and innovation

The 6 priority areas are underpinned by 1 base and 5 pillars. The base provides the foundation to the delivery of this strategy and refers to enhancing our communications, awareness and education of health inequalities for our people, our patients and our local communities.

The five pillars encompass behaviours, models of practice and a general ethos/culture shift which when implemented will support all the work across all 6 priority areas.

These pillars include:

- Understanding our communities – to ensure accurate, complete and timely access to population health data in conjunction with community voices to better understand the health inequalities and where to focus our action.

- Connecting people – to work closely with partners and build on existing relationships, networks, and trust. This will ensure work is aligned and supported and will prevent silo-working allowing health inequalities to be addressed using a whole system approach.

- Model of delivery – to move towards a more needs-led, compassionate social model of care and to use co-production to improve existing services and/or develop new services based on the needs of our communities.

- Access to and experience of services – to focus on the Core20PLUS5, ensuring targeted support is provided for the Core20 and PLUS groups, including inclusion health groups, particularly (but not exclusively) across the 5 service areas for adults and children and young people.

- Leadership and accountability – strong leadership and clear accountability and governance structures will support a culture shift and help to embed health inequalities in everything we do, acknowledging that our staff may also be experiencing health inequalities.

Base

To enhance communications, awareness, and education of health inequalities.

Pillars

- Our pillars are circular and interconnect with one another.

- Understanding our communities

- Connect people

- Access to and experience of services

- Model of delivery

- Leadership and accountability.

Priorities

- Prevention

- Elective Care Pathways

- Urgent and Emergency Care

- Maternity/Best Start in Life

- Children and Young People

- Research and Innovation

To support the delivery of our strategy, we have also provided a 3-tier framework. The framework outlines work that we can do to tackle health inequalities by:

- Increasing support/developing new services,

- Improving our existing services, and

- Influencing the wider determinants of health in our Anchor Institution role. This framework will support teams, services, and divisions to guide thinking/act as a prompt for action.

We have also developed an associated action plan which outlines our planned areas of work, associated key performance indicators and anticipated timeframes for completion.

Three-tier framework

DBTH’s 3-tier framework for improving health and tackling health inequalities (adapted with permission from Barnsley’s Integrated Care Partnership framework)

Tier 1 – Increase support

The first layer of action is to increase engagement, opportunities, services and support to address the key drivers of health inequalities for people in need and making every contact count.

To ensure people have access to support that prevents them getting sick and reduces the drivers of inequality in their life, we need our teams (both clinical and non-clinical) across the Trust to be discussing health inequalities, to highlight where gaps in knowledge may be and/or to identify potential areas for improvement.

Tier 2 – Improve care

The first layer of action is to increase engagement, opportunities, services and support to address the key drivers of health inequalities for people in need and making every contact count.

The first layer of action is to increase engagement, opportunities, services and support to address the key drivers of health inequalities for people in need and making every contact count.

To ensure people have access to support that prevents them getting sick and reduces the drivers of inequality in their life, we need our teams (both clinical and non-clinical) across the Trust to be discussing health inequalities, to highlight where gaps in knowledge may be and/or to identify potential areas for improvement.

Tier 3 – Influence others

The first layer of action is to increase engagement, opportunities, services and support to address the key drivers of health inequalities for people in need and making every contact count.

To ensure people have access to support that prevents them getting sick and reduces the drivers of inequality in their life, we need our teams (both clinical and non-clinical) across the Trust to be discussing health inequalities, to highlight where gaps in knowledge may be and/or to identify potential areas for improvement.

Key Terms

Some key terms are (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, 2021):

- Health Inequalities: Avoidable differences in health outcomes between groups or populations – such as differences in how long we live, or the age at which we get preventable diseases or health conditions.

- Equity: We want fair outcomes for everyone. What is important is addressing avoidable or remediable differences in health between groups of people. To achieve health equity, some groups may need more or different support or resources to achieve the same outcomes. Ideally, the barriers to good health would be removed for everyone, so adjustments wouldn’t be required – however, this is not always possible.

- Equality: We want everyone to have equally good health. However, the term ‘equality’ is sometimes used to describe equal treatment or access for everyone regardless of need or outcome.

- Access: Ensuring everyone can access services equitably (that is according to need) is a key priority for the NHS. To achieve this, consideration needs to be given to access to information, services and support. Central to this is enabling people to access the right service at the right time for them, reducing variation in the avoidable use of urgent support such as accident and emergency services through better access to preventative care.

Introduction

Welcome to DBTH’s new Tackling Health Inequalities Strategy!

At Doncaster and Bassetlaw Teaching Hospital Foundation Trust (DBTH), we have the vision of being “Healthier together – delivering exceptional healthcare for all.”

To read about our core values and vision, visit https://www.dbth.nhs.uk/about-us/our-values-and-vision/

This strategy also aligns closely to the DBTH Way and our We Care values. Leading by example and role-modelling the DBTH Way and our We Care values will provide an appropriate ethos and a supportive environment for health inequalities work to be undertaken more effectively.

What are Health Inequalities?

Health inequalities are “avoidable, unfair and systematic differences in health between different groups of people” (The Kings Fund, 2022). They mean that some population groups have significantly worse health experiences and outcomes than others. These differences can be due to a range of factors including a person’s social, economic and environmental circumstances – and we know that greater deprivation in any of these factors is associated with an increased risk of becoming ill earlier and dying younger. People with certain characteristics, such as certain ethnicities, sexual orientation, age and disabilities, also have a lower chance of living a long and healthy life compared to others. This is often due to the exclusion from society that people with these characteristics face.

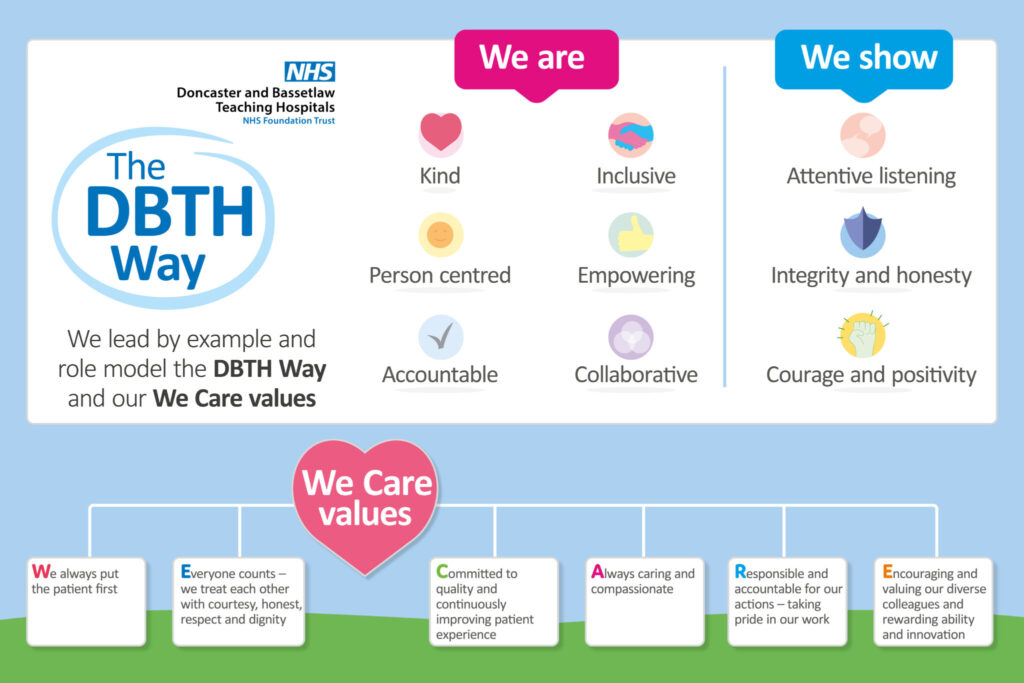

Comparing life expectancy in Doncaster and Bassetlaw between the most and least deprived communities:

In Doncaster: men living in the most deprived areas die on average 10 years earlier than men living in the least deprived areas; for women this difference is 8 years.

In Bassetlaw: men living in the most deprived areas die on average almost 8 years earlier than men living in the least deprived areas; for women this difference is 6 years.

A wide range of factors influence our ability to be healthy. These factors often overlap with each other and are often outside the control of individuals themselves.

Figure 1 below demonstrates the complex interplay between the wider determinants of health (e.g. income, housing, built environment, education), psychosocial factors (e.g. isolation and social support), health behaviours (e.g. smoking, drinking alcohol), and the resulting physiological impacts (e.g. high blood pressure, anxiety and depression).

Systems map of the causes of health inequalities

The following factors are interlinked and can impact one another.

Health and Wellbeing and physiological impacts

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol

- Anxiety/depression

Health behaviours

- Smoking

- Diet

- Alcohol

Psycho-social factors

- Isolation

- Social support

- Social networks

- Self-esteem and self-worth

- Perceived level of control

- Meaning/ purpose of life

Wider determinants of health

- Income and debt

- Employability / quality of work

- Housing

- Education and skills

- Natural and built environment

- Access to goods / services

- Power and discrimination

Why do we need to tackle Health Inequalities?

Addressing health inequalities is a matter of social justice – some have less health than others and that is largely to do with structural factors not individual choices. It is unfair that just by virtue of someone’s ethnic background or place of birth they should experience poorer health.

In addition, these avoidable differences in health pose a huge cost to societal, economic and health systems. Health inequalities contribute to increased demand for healthcare – as investment and action in the cost-effective approaches to maintain health and wellbeing shrinks, the need for less cost-effective diagnostic and treatment services grows. When wider costs are factored in, such as loss of workforce productivity, the overall economic burden of preventable and premature illness is staggering – around £31 billion a year in lost productivity and between £20 and £32 billion a year in lost tax revenue and benefit payments (Public Health England, 2021).

What does this mean for the NHS?

The higher burden of disease experienced by women living in the most deprived neighbourhoods costs the NHS 22% more per person than women living in the least deprived neighbourhoods, despite having shorter life expectancy (or £400 per person per year in secondary care costs). For men, this figure is 16% per person (or an additional £300 per person per year in secondary care costs). This results in an additional spend of £4.8 billion per year, almost 20% of the total hospital budget (Asaria M, 2016), without taking into account additional costs, including social care provision.

Health is therefore a major determinant of economic performance and prosperity. Consequently, taking action on health inequalities:

- improves the quality of lives of individuals

- reduces cost to the NHS and social care system of treating and caring for people with preventable conditions

- benefits the wider economy (Marmot, 2010).

Much of the way our national and local systems have been set-up has inadvertently contributed to the increase in health inequalities – we therefore need to do things differently. Figure 2 (see page 12 below) demonstrates the difference between equality and equity.

By treating people equally, e.g. offering an NHS which is free at the point of use to all (or providing everyone with the same sized box to see the ball game, as per the first image in Figure 2 below), we are assuming everyone has the same ability to access our services.

In reality, some groups have significant barriers to accessing healthcare, such as physical disabilities, poor mental health, language or cultural barriers, mistrust of healthcare systems, inability to pay for transport to get to hospitals, other more significant life priorities, e.g. caring responsibilities, work, finances etc.

By treating everyone equally, we are contributing to the widening of health inequalities as we’re not taking into account these systemic barriers – those who can, will access health services and get better health outcomes as a result; those who can’t, will be left with worsening health issues.

Instead, if we offer more targeted supports for those who need it, i.e. if we treat people equitably based on their needs, then we can help to ensure equal access (or providing the right number of boxes to each person to ensure they can see the ball game equally well, as per the second image in Figure 2), which in turn will help to reduce health inequalities.

The third image in Figure 2 is where we should aspire to be – the systemic barriers (in this case the wooden fence) have been removed so no extra supports are needed as everyone can see the ball game equally well already. It is predominantly national level shifts in policy and infrastructure change that are needed to remove the systemic barriers and address the cause of the inequalities, however, there are lots of things we can do locally which will make a difference.

This strategy therefore highlight’s DBTH’s commitment to tackling health inequalities and lays out the key areas of focus for DBTH for the next five years.

Equality versus equity

In the first image, it is assumed that everyone will benefit from the same supports. They are being treated equally.

In the second image, individuals are given different supports to make it possible for them to have equal access to the game. They are being treated equitably.

In the third image, all three can see the game without any supports or accommodations because the cause of the inequity was addressed. The systemic barrier has been removed.

Health Inequalities in Doncaster and Bassetlaw

Table 1 (see page 13 below) presents a few key figures which demonstrate the extent of some of the health inequalities facing people from Doncaster and Bassetlaw. To summarise:

- Over 40% of the Doncaster population and 21% of the Bassetlaw population are living in the 2 most deprived Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) deciles nationally, i.e. the “Core 20”.

- In Doncaster, almost a quarter of our children are living in low-income families, and in Bassetlaw it’s almost a fifth.

- In terms of life expectancy for males and females, both Doncaster and Bassetlaw are lower than the national average.

- The difference in life expectancy from the most to the least deprived areas in Doncaster is almost 10 years for males and 8 years for females. For Bassetlaw, the differences in life expectancy from the most to least deprived is almost 8 years for males and 6 years for females. Just to put that into context – a man from the most deprived area of Doncaster is living on average 11 years less than a man from the least deprived area. Similarly, a man living in the most deprived area of Bassetlaw is living on average 9 years less than a man from the least deprived area.

- Healthy life expectancy for males and females in both Doncaster and Bassetlaw is lower than the England average and if we just pull out the data here for females in Doncaster, we can see that the amount of time females are living in good health (i.e. their healthy life expectancy) is 56 years, but their average life expectancy is 81 years. This means that they are living for on average 25 years in poor health and during that time, will likely be accessing a range of health services.

Our Strategy

Our Tackling Health Inequalities Strategy 2023-2028 has been developed in alignment with various other national and local plans/strategies. By aligning our strategy with others, we will ensure that we are not producing a “standalone” strategy, but one that is working alongside and with our partners across the system.

This will mean that work is not duplicated and where relevant we can collaborate, share resources (human and financial), and provide support when needed. Other plans and strategies we have considered during the development of our strategy include:

- The NHS Long Term Plan, which clearly sets out commitments for action that the NHS needs to take on improving prevention and tackling health inequalities

- NHS England’s “Tackling inequalities in healthcare access, experience, and outcomes: Actionable Insights”

- Core20PLUS5 – a national framework for addressing healthcare inequalities

- NHS South Yorkshire Integrated Care Board (ICB) NHS Joint Forward Plan for South Yorkshire

- NHS Nottingham and Nottinghamshire ICB NHS Joint Forward Plan

- Doncaster 1 Plan 2023/24

- Bassetlaw Place Plan

It’s worth highlighting the detail relating to the Core20PLUS5 framework as we will draw on this throughout our strategy.

Figure 3 (see below) depicts the Core20PLUS5 framework for adults. The “Core20” refers to the most deprived 20% of the national population as identified by the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). The key word there is national.

For clarity, the IMD score ranks small geographical areas from most to least deprived. It then groups them together into 10 equal groups (or deciles) – from 1 (most deprived) to 10 (least deprived). The 20% most deprived areas nationally are therefore those in deciles 1 and 2. However, in Doncaster, for example, 41% of our population fall into the 2 most deprived deciles nationally (as shown in Table 1 above).

The “PLUS” refers to chosen population groups experiencing poorer than average health access, experience and/or outcomes who may not be captured in the Core20 alone and would benefit from a tailored healthcare approach. See appendix 1 for a list of “PLUS” groups (please note, this is not an exhaustive list).

“PLUS” groups can include people with a protected characteristic, people in socio-economically deprived populations, people from specific geographies (the places where we live), e.g. urban/rural/coastal locations, and inclusion health and vulnerable groups, e.g. Gypsy, Roma, Traveller communities, people experiencing homelessness, offenders, sex workers. When individuals, groups or communities face more than one of these issues (intersectionality), then the risk of health inequalities is further increased.

The “5” refers to 5 key clinical areas of health inequalities and includes:

- Maternity services

- Severe mental illness

- Chronic respiratory disease

- Early cancer diagnosis

- Hypertension case-finding

Finally, smoking cessation has been identified as something that would impact all 5 key clinical areas.

Content out of date? Information wrong or not clear enough? Report this page.